15M-inspired responses to issues raised during the IWM Summer School, Austria

15M-inspired responses to issues/questions raised during the Institut für die Wissenschaften vom Menschen (IWM) Summer School at Burg Feistritz, Austria

By Pablo Ouziel

Entry number two: ‘The tragedy of the commons’

On one of the days at Feistritz castle, Holy Case, Associate Professor of History at Brown University, gave a talk in which she asked whether determining the relationship between democracy and demography was a thought problem or a real problem.

In her talk, Case presented our civilizations as shipwrecked in the global ecological disaster. Playing with the idea of metaphor she painted a picture of the current environmental crisis in which the more fortunate and capable passengers are able to escape on lifeboats, while others try to climb into the already overwhelmed and defective vehicles. At that point, those in the boats are faced with the dilemma of what to do. If they take the others, everyone sinks, if they do not, they have to live with their decision. Ultimately, some can be saved or everyone can drown.

Case was drawing on ecologist Garrett Hardin´s Lifeboat ethics: The case against helping the poor (1974). She also used William Forster Lloyd’s Two lectures on the Check to population (1833) to ask if we all should have equal right to an equal share of the resources. According to Lloyd “to a plank in the sea, which cannot support all, all have not an equal share.” It is the lucky individuals who appropriate the plank first that have the right to keep it for themselves at the expense of the remainder.

It is in this essay that Lloyd first raises the idea of the problem of the commons, describing the effects of unregulated grazing on common land. According to him, it is only through enclosure that land can be protected from over-usage. Nevertheless, it is only a century later in 1968, that Hardin popularizes the idea of the tragedy of the commons with his essay titled The Tragedy of the Commons.

As Case suggested during her talk, global warming is framed as a tragedy of the commons. Yet, I think it important to suggest that the co-regulated commons operate much like a dance that those bent on enclosing have not been able to understand. In fact, it is the tragedy of privatization, I will argue following James Tully, that is leading to accelerated climate change and environmental destruction.

As Tully has argued in Two ways of realizing justice and democracy: linking Amartya Sen and Elinor Ostrom (2013), from the space of elite democracy the institutional structure of the contemporary practice of democracy limits realization-focused democracy unjustly in two ways. First, it limits or eliminates alternative democracies. And, second, it limits democracy internally by pre-emptively privatizing a range of social and economic activities. This Tully argues, excludes realization-focused democracies from being brought under the democratic control of those who are engaged in and affected by them, and restricts democracy to public reasoning and representative government. As Tully points out, through privatization and shielding, a range of social and economic activities are left out of the democratization process and this causes three of the tragic global injustices we are currently living through. First, Global South exploitation, inequality and poverty. Second, the rapidly accelerating destruction of the environment. And third, global warming and climate change.

In his article Tully suggests that if we orient ourselves from this different democratic-commons perspective, “the injustices of the ‘institutional structure of the contemporary practice of democracy’ comprise what we can call ‘the tragedy of privatization’, in contrast to the thesis of the ‘tragedy of the commons’ that has served to legitimate the coercive globalization of this institutional structure since Hobbes.” Basically, what I gather from Tully’s work is that it is not the commons that is the main cause of our current environmental disaster but the enclosures that have been imposed on our common land (earth).

I think Tully makes a valuable observation in this work, which speaks to how people in 15M in Spain (that occupied public squares in 2011) see humans and their relationships with each other. Rather than seeing humans as independent, insecure, and unable to organize without violence and domination, those being 15M in Spanish public squares and beyond, defend and enact cooperative and interdependent relationships of contestation and integration. In doing this, 15M presents a tentative and alternative imaginary of social relationships and power configurations which rejects the tragedy of the commons and embraces commoning practices. It is through these kinds of relationships that those being 15M think systems of violent conflict can be transformed and replaced.

In a sense, 15M defends and enacts the kind of nonviolent agonistics which Richard Gregg and Mahatma Gandhi advocated for throughout their lives. Nevertheless, this mode of being of collective presences like 15M has often been misunderstood. Therefore, in order to help better understand them I suggest that it is best to take a critical stance on Hobbes and read Peter Kropotkin as a alter-narrative to the much praised myth of the Leviathan.

In Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution (1902), Kropotkin speaks of mutual aid to describe the kind of power relationship we see today enacted by 15M. He points out that, despite the systematic destruction of mutual aid institutions over the centuries, such institutionality, together with its habits and customs has survived. According to Kropotkin, millions of individuals not only continue to enact mutual aid institutions but are reconstituting them where they have perished. This, he is saying in 1902, but arguing along similar lines in the present, Paul Hawken in Blessed Unrest, How the Largest Movement in the World Came into Being and Why No One Saw it Coming (2007), has suggested that these mutual aid networks constitute the largest informal, symbiotic fellowship of engaged citizens in the world. As Hawken puts it, it makes up a network of human beings “willing to confront despair, power, and incalculable odds in an attempt to restore some semblance of grace, justice, and beauty to this world.”

Following from this and in multilogue with Kropotkin, Hawken, and millions of other participant-thinkers across time, 15M reveals the healthy existence of mutual aid institutionality within Spain. As a reminder, the popular 15M slogan ‘Vamos lentos porque vamos lejos’ (We go ever so slowly because we are going on forever) plays tribute to the autotelic relation between means and ends found in 15M’s joining hands relationships. I think of these joining hands relationships as exemplary responses and antidotes to neoliberalism and right-wing populism. Through them, citizens are challenging modernity’s foundational and violent forms of subjectivity, and building a counter-modernity “within, around, and against” the dominant institutions of their society. In this blog entry, I am not going to describe what these joining hands relationships entail because of space constraints, but if you are interested in reading about them in detail I have a forthcoming book on 15M in which I describe them in detail. The name of the book is Democracy here and Now: The exemplary case of Spain.

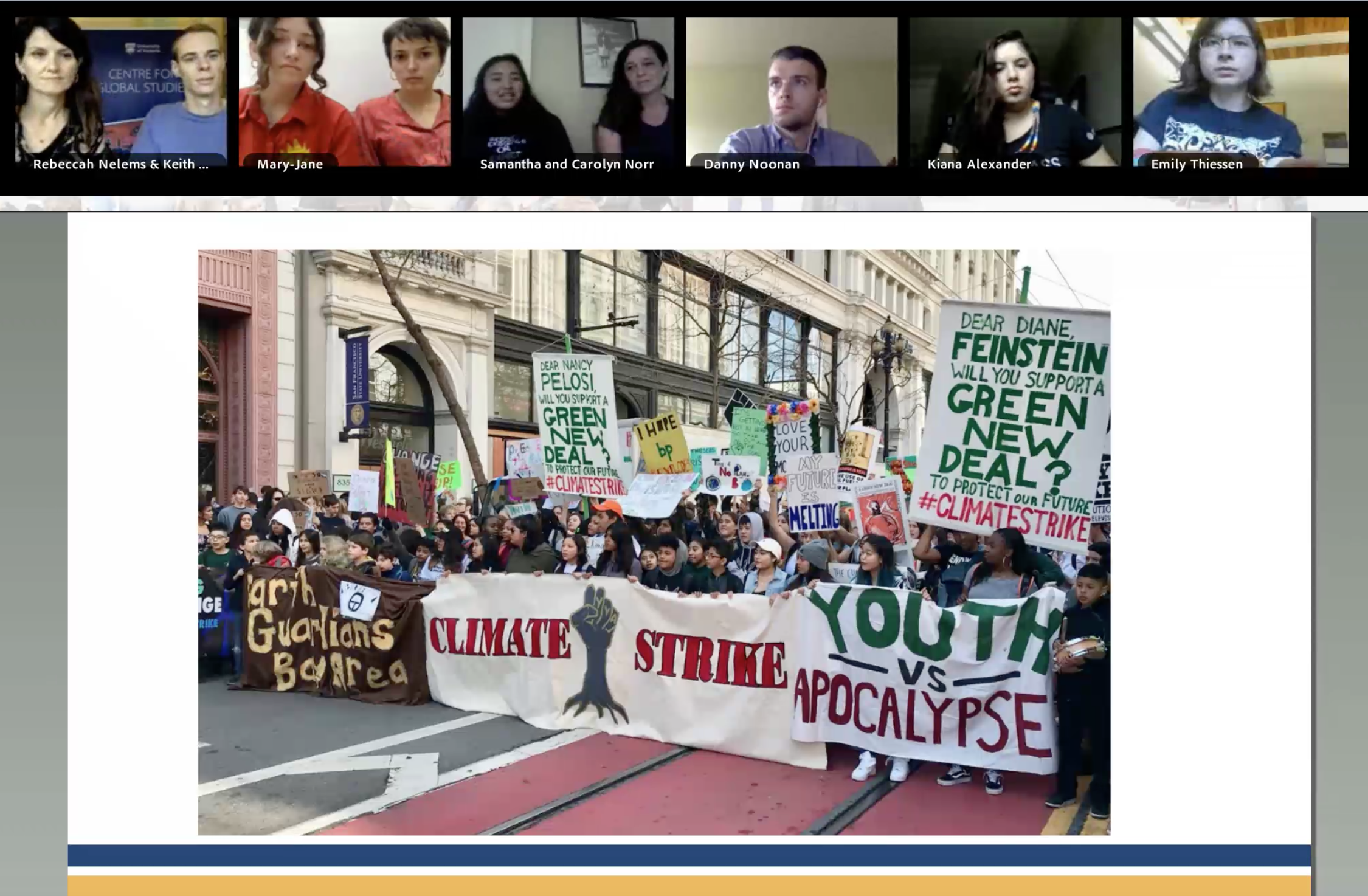

What is important for the purpose of this blog is to note that working around the enclosure of the commons, 15M continues to institute commoning practices in places were the commons seemed to have been lost. It is also important to highlight that 15M is just one recent example in Spain. Across the globe we can see examples and exemplars of commons and commoning practices that present a clear alternative view to that which Hardin popularized in his 1968 text. It is in these alternatives that one can perhaps tentatively respond to Case by suggesting that the problem we have when thinking about democracy and demography and how to overcome the climate crisis is not a real problem but a problem of thought. The reason I say this is that when humans have opted to think of these issues from the position of mutual aid, common responsibility and care, the concerns and responses have been different in kind.

Acknowledging the fact that there are many examples of the commons having historically worked and survived despite the enclosing logic of privatization, here are just some minor examples from the Spanish civil war which stem out of my research within 15M. What is interesting about this period is that a society under attack by totalitarian forces responded by sharing-with and mutual care and entered into gift-reciprocity relationships which obtained remarkable results.

On July 18, 1936, a military coup marked the beginning of the Spanish Civil War. During the very early days of the military outbreak, many workers who were actually on strike, soon began to reclaim their production capabilities; seizing corporations and organizing themselves into assembly-run collectives. Even strategic industries such as the oil company CAMPSA were collectivized. A mere week following the military uprising, different self-organizing demoi were running public transportation, the train system, water, and energy sources. In many cases, collectivization was so far reaching it encompassed the whole process of extraction or cultivation, production, distribution, and administration. In metropolitan areas, agrarian land was being collectivized.

In Barcelona, the central fruit and vegetable market in the neighbourhood of the Born was collectivized; distribution from the countryside was also facilitated through collectives. In Montblanc, articles were bought with a new collectivized currency. Some collectives used central storage areas where everyone took what was needed. In others, such as Llombay (Castellón), goods were distributed based on family needs. In most of the collectivized areas, when shortages existed, priority was given to children, the sick, elderly people, and women. In Seros, unmarried people were fed in communal kitchens and were given clean clothes. When they married, the community helped them set up their new family homes. In Graus, the population paid for newly-weds to go on honeymoons. Relationships in collectives were deeply democratic. In Hospitalet de Llobregat, they celebrated general assemblies every three months. In Ademuz, assemblies were celebrated every Saturday and, in Alcolea de Cinca, whenever anyone in the community deemed an assembly necessary.

During this period, a social revolution was taking place within the broader context of a civil war. In this sense, many collectives supported the Republican war effort. Nevertheless, most collectives were predominantly focused on developing their constructive programs towards a new society based on commoning, and constructed through nonviolent, cooperative and democratic principles. George Orwell, in Homage to Catalonia (1938) speaks of the Spanish Militias fighting at the Aragon front. Referring to the experience there as an experiment in classless society, he says the following: “In theory it was perfect equality, and even in practice it was not far from it.” It is interesting that as he brings the book to an end Orwell also points to the fact he had found himself in “the only community of any size in Western Europe were political consciousness and disbelief in capitalism were more normal than their opposite” a state of affairs which could not last because it was only a temporary and local phase in the enormous power-over game being played out over the whole surface of the earth.

With this post, I am not expecting every reader to all of a sudden embrace the idea of the commons, what I do hope, however, is that it will give a glimpse of one alternative to our current hegemonic understandings on how we as humans have interacted with each other over time and how we might interact moving forward as the twin crises of democracy and the environment continue to unfold.

In my next entry, I will write about ‘spontaneity and collective presences,’ this was another reoccurring issue during the multilogue at Burg Feistritz, which my work within 15M has revealed to be in need of serious attention.